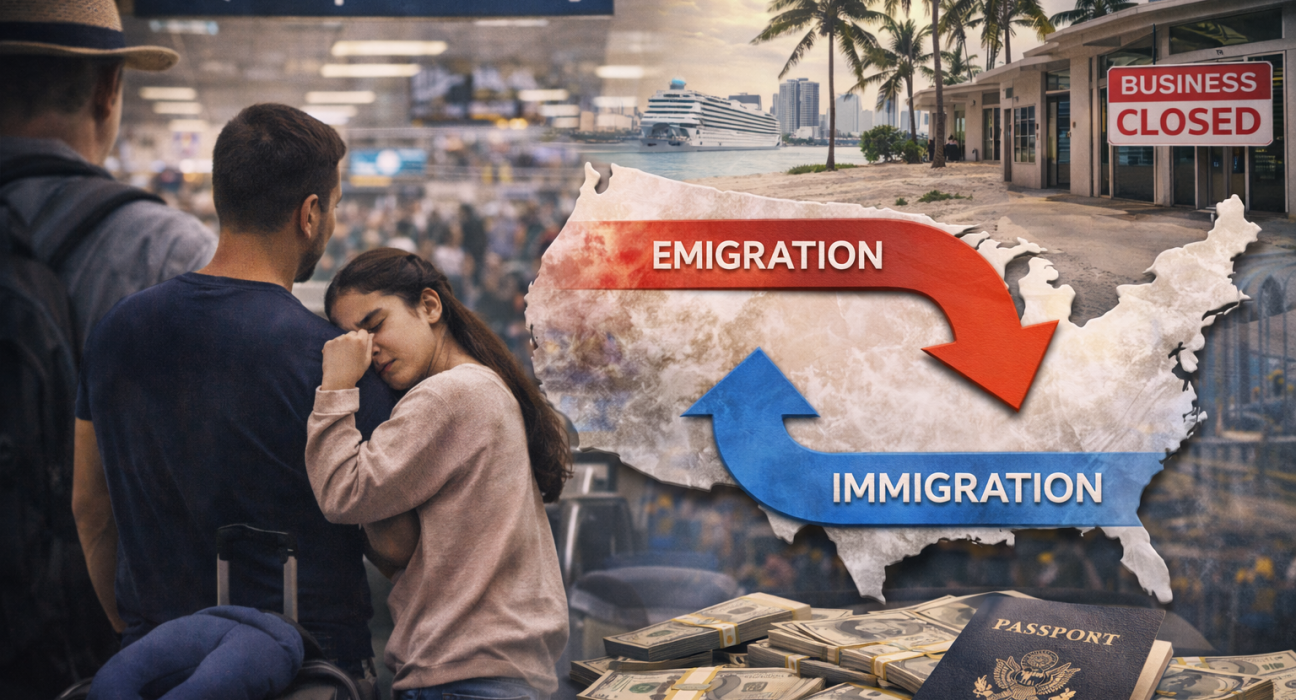

For the first time in more than 50 years, the United States has experienced negative net migration, meaning more people left the country than entered it during the most recent measurement period, according to ABC News and U.S. Census–based analysis. This reversal marks a significant demographic shift with wide-ranging consequences for states, industries, and long-term economic planning — particularly for regions that rely heavily on tourism, service labor, and population growth to sustain local economies.

What Negative Net Migration Means

Net migration accounts for immigration minus emigration, including citizens leaving the U.S., foreign nationals departing, and fewer new arrivals. While population growth has slowed before, the U.S. has not recorded a net loss driven by migration since the early 1970s.

Demographers attribute the shift to a convergence of factors, including:

- Tighter immigration enforcement and administrative bottlenecks

- Global economic uncertainty and stronger growth opportunities abroad

- Rising cost of living, housing, and healthcare in the U.S.

- Remote work allowing skilled workers to relocate internationally

- Increased deportations and voluntary departures

While natural population growth (births minus deaths) remains positive, it has slowed significantly, meaning migration now plays a more critical role in sustaining workforce size and consumer demand.

Impact on Tourism-Dependent States

States that rely heavily on tourism — including Florida, Nevada, Hawaii, California, Arizona, and New York — may feel the effects most acutely.

Tourism economies depend on:

- A large service-sector workforce (hospitality, food service, transportation)

- Seasonal and immigrant labor

- Population churn that sustains housing, retail, and entertainment sectors

Negative net migration can reduce labor availability, drive up wages in the short term, and increase operating costs for hotels, restaurants, cruise lines, theme parks, and event venues. In areas already facing labor shortages, this may result in reduced services, shorter operating hours, or higher prices for visitors.

In states like Florida and Nevada, where tourism accounts for over 15% of state GDP, even modest population declines can ripple outward — affecting tax revenues, airport traffic, convention bookings, and small business viability.

Broader Industry Effects

Beyond tourism, several industries are particularly exposed:

Hospitality & Food Services:

Already among the hardest hit by labor shortages, these sectors rely disproportionately on immigrant and mobile workers. Fewer arrivals can slow expansion plans and reduce service capacity.

Construction & Real Estate:

Population decline dampens housing demand, particularly in urban cores and resort markets. This can cool construction pipelines and reduce state and local revenue tied to development.

Healthcare & Elder Care:

Many healthcare systems depend on foreign-born workers, especially in home health and long-term care. Reduced migration may strain systems serving aging populations — particularly in Sun Belt states.

Higher Education & Research:

International students contribute billions annually in tuition and local spending. Declines in student inflows affect university budgets and innovation ecosystems.

Is This a Victory for the U.S.?

Whether negative net migration is a “victory” depends largely on perspective.

Arguments Framing It as a Positive Shift

Supporters of stricter immigration policies argue that negative net migration:

- Reduces pressure on housing, schools, and infrastructure

- Increases bargaining power and wages for domestic workers

- Allows time to modernize immigration systems

- Signals stronger border and enforcement control

From this view, a pause or reversal in migration could be seen as an opportunity to recalibrate labor markets and prioritize workforce participation among existing residents.

Arguments Viewing It as a Net Loss

Most economists and demographers caution that sustained negative net migration poses long-term risks, including:

- Slower economic growth due to workforce contraction

- Reduced innovation and entrepreneurship

- Accelerated population aging

- Shrinking tax bases in already fragile regions

Historically, immigration has been a primary driver of U.S. economic expansion, productivity growth, and global competitiveness. A prolonged downturn in migration could weaken the country’s relative position compared to nations actively courting global talent.

Regional Winners and Losers

Potential Losers:

- Tourism-heavy states

- Urban centers dependent on population density

- Regions with aging populations and low birth rates

Potential Short-Term Winners:

- Some domestic workers facing less labor competition

- Communities experiencing reduced housing pressure

- Infrastructure systems operating below capacity

However, most analysts emphasize that short-term gains may be offset by long-term structural challenges if migration does not rebound.

Global Context

Other advanced economies — including Canada, Australia, and parts of Europe — are actively increasing immigration to counter aging populations and labor shortages. If the U.S. diverges from this trend, it may face heightened competition for global talent, tourists, and investment.

At the same time, remote work and digital nomadism are reshaping global mobility. Highly skilled workers increasingly choose jurisdictions offering lower costs, favorable tax regimes, or stronger social safety nets — intensifying the competition among countries.

Future Projections

Short Term (1–2 years):

Tourism and service industries may face higher labor costs and operational strain. States may increase visa advocacy or workforce training initiatives.

Medium Term (3–5 years):

If migration remains negative, some regions may see declining consumer demand and slower economic growth, prompting policy reconsideration.

Long Term:

Sustained negative net migration would likely force a fundamental rethink of immigration, workforce, and economic strategy — particularly as the U.S. population continues to age.

Conclusion

Negative net migration marks a historic inflection point for the United States. While some view it as evidence of stronger enforcement or reduced strain, most evidence suggests it presents significant economic challenges, especially for states and industries built on mobility, tourism, and growth.

Whether this moment becomes a strategic reset or a warning sign will depend on how policymakers, businesses, and communities respond — and whether the U.S. ultimately reasserts itself as a destination for global talent and travelers.