For decades, history textbooks in American classrooms have presented a selective version of technological progress—one that often centers white inventors while leaving out the significant contributions of Black innovators. This omission is not accidental. It reflects systemic racism, discriminatory patent laws, and the cultural tendency to simplify history into neat narratives that favor dominant groups.

Before the Civil War, enslaved Black inventors were legally barred from holding patents, meaning their creations were often stolen or claimed by their enslavers. Even after emancipation, many faced barriers that prevented them from securing credit or commercializing their work. As a result, their contributions were minimized, forgotten, or deliberately excluded from official accounts.

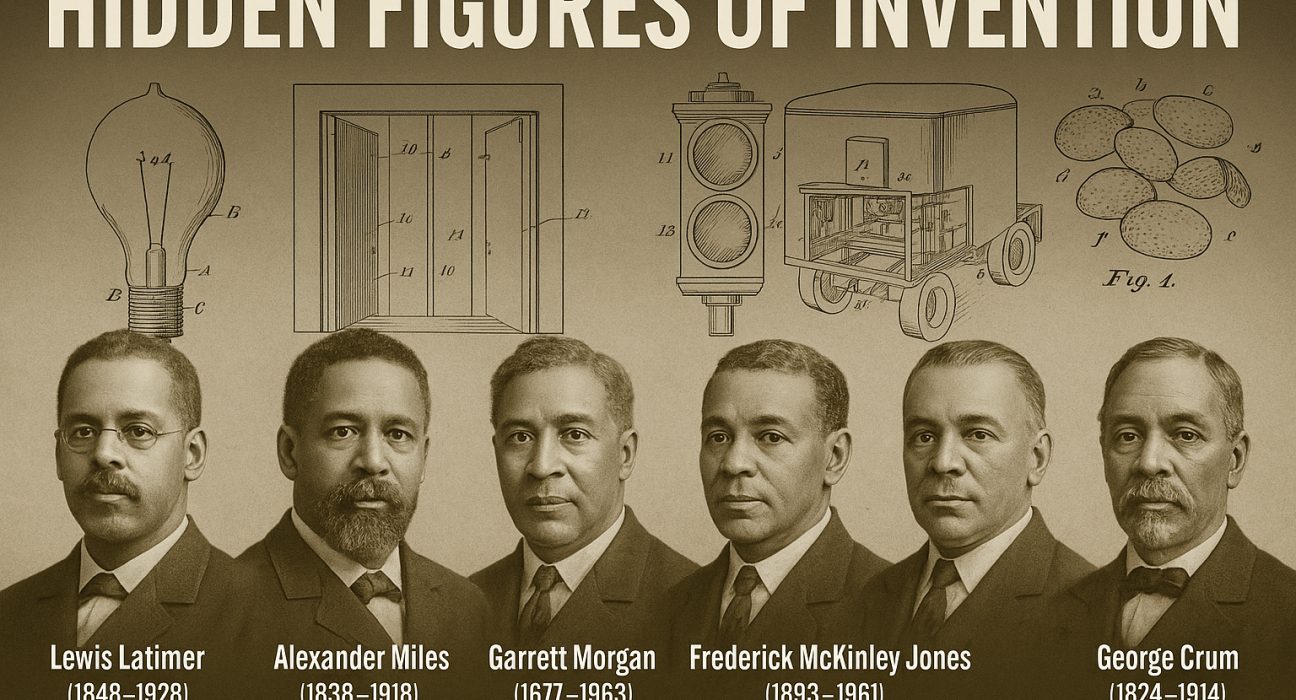

Take the light bulb, for example. Thomas Edison is celebrated as its sole inventor in most textbooks. Yet Edison’s original design burned out quickly. It was Lewis Latimer, a Black inventor and son of escaped slaves, who developed a carbon filament that made light bulbs practical for everyday use. Without Latimer’s improvement, electric lighting would not have become the household standard it is today.

Similarly, the telephone is credited to Alexander Graham Bell, but his early model was barely functional. Latimer again played a pivotal role—producing the technical drawings for Bell’s patent and later improving the transmitter so voices could travel longer distances with clarity. These were not mere “tweaks” but essential breakthroughs that made the invention commercially viable.

The traffic light, a cornerstone of road safety, also has a hidden history. While early signals existed, Garrett Morgan, a Black inventor from Cleveland, patented an improved three-position signal in 1923, adding a crucial “warning” interval between “Stop” and “Go.” This design dramatically reduced accidents and laid the foundation for the modern system.

Morgan also developed the first widely used gas mask—a “safety hood” designed in 1914, years before chemical warfare became a battlefield reality. His invention saved lives in mining disasters, fires, and rescue operations, and was later adapted for military use.

Other examples abound. Alexander Miles patented automatic elevator doors in 1887, preventing deadly accidents by ensuring that both the shaft and car doors closed securely. Frederick McKinley Jones revolutionized the transport of food and medicine by inventing portable refrigeration for trucks, ships, and planes in 1940. Even in the culinary world, George Crum, a Black and Native American chef, created the potato chip in 1853—though his heritage is often erased in popular retellings.

The omission of these figures from educational materials is more than an oversight—it is a distortion of history. By erasing Black inventors from the narrative, society reinforces the false idea that innovation is the domain of a privileged few. This exclusion also denies Black communities the rightful pride and inspiration that comes from knowing their ancestors helped shape the modern world.

Correcting the record is not simply about adding names to a list—it’s about rewriting the story of progress to reflect the truth. The legacy of these hidden figures is not one of obscurity, but of resilience, ingenuity, and brilliance that deserves permanent recognition in our classrooms, museums, and collective memory.

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| Thomas Edison is credited as the “inventor of the light bulb” in 1879. | Edison did patent a version of the bulb, but it was impractical — it burned out quickly. Lewis Latimer, a Black inventor and son of escaped slaves, invented a carbon filament (patented in 1881) that made bulbs last much longer, making electric lighting practical and affordable. Without Latimer’s innovation, the light bulb wouldn’t have been viable for mass use. |

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876. | Bell’s original design had serious flaws. Lewis Latimer (again!) drafted the drawings for Bell’s patent and later improved the transmitter, allowing voices to be heard clearly over longer distances. His engineering skill was crucial to the phone’s commercial success. |

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| The traffic signal was invented in the early 20th century, often credited vaguely to “early automotive safety engineers.” | Garrett Morgan, a Black inventor from Cleveland, patented an improved three-position traffic signal in 1923. His design added a “warning” position between “Stop” and “Go,” which dramatically reduced accidents — the foundation of modern traffic lights. |

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| Elevators became safe thanks to “innovations in automatic doors” by the Otis Elevator Company. | Alexander Miles, a Black inventor, patented an automatic door mechanism in 1887 that closed both the shaft and the elevator door simultaneously — preventing deadly falls. His design is the ancestor of modern elevator safety systems. |

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| The gas mask was developed for soldiers during World War I. | Garrett Morgan (yes, the same man who invented the improved traffic light) created a “safety hood” in 1914, years before WWI gas masks. His invention saved lives in fires, mining disasters, and chemical accidents — and was adapted for wartime use. |

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| Potato chips were invented by a chef named George Crum in 1853 — if they’re mentioned at all, it’s often as a quirky anecdote. | The truth: George Crum was a Black and Native American chef in New York who invented chips accidentally after a picky customer complained about thick fries. The story is sometimes told without acknowledging his racial identity, making it sound like just another “American invention.” |

| Textbook Version | Real History |

|---|---|

| Refrigerated transport developed as the meatpacking industry expanded in the 20th century. | Frederick McKinley Jones, a Black inventor, patented a portable refrigeration unit in 1940 that allowed trucks (and later ships, trains, and planes) to safely transport perishable goods — revolutionizing the food and medical industries. |